Sparta, TN, aka Bluegrass USA. | #bluegrasstrails

Part of the mygrassisblue.com #BluegrassTrails series, on the trail of bluegrass history and its pioneers/early protagonists.

Liberty Square during the 1-day ‘A Lester Flatt Celebration’ gathering in Sparta, Tennessee, aka Bluegrass USA, the hometown of Lester Flatt (and Benny Martin). October 14, 2017.

– SpartaTN.gov

The guitar-shaped Lester Flatt monument on Bockman Way, Sparta, Tennessee. October 15, 2017.

We probably would have stopped by anyway, but we wouldn’t have been in such a hurry to do so. As it turns out, it was the proximity of the one-day musical celebration of Sparta’s most famous native son that is the town’s annual A Lester Flatt Celebration that was reason enough to ensure we busted a gut in driving the 1,937 miles (3,117 kilometres) that we drove to get here, via an east coast road trip and a deep Deep South detour (Jacksonville east and New Orleans deep), just six days after saying goodbye to the four-day Outer Banks Bluegrass Island Festival in Manteo, North Carolina, only 650 miles away at its most direct. Needs must.

A Lester Flatt Celebration. Oldham Theater, Liberty Square, Sparta, Tennessee. October 14, 2017.

It took a bit of searching out (we almost gave up looking) but we eventually found the small bronze plaque that marks the final resting place of Lester Raymond Flatt in the peaceful Oaklawn Memorial Cemetery 3 miles from Sparta’s Liberty Square.

Lester Flatt’s grave in Oaklawn Memorial Cemetery, Sparta, Tennessee. October 15, 2017.

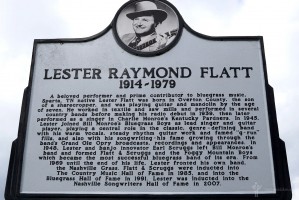

Lester Flatt | IBMA Hall of Fame Bio

“A Conversation with Lester Flatt,” interview with Vernon, Bill in Muleskinner News, August, 1972.

IBMA Hall of Fame Induction | 1991

Born | June 19, 1914 in Duncan’s Chapel, Overton County,Tennessee

Died | May 11, 1979 in Nashville, Tennessee

Primary Instrument | Guitar, Mandolin

Lester Flatt‘s grandfatherly emceeing style, relaxed southern singing voice, solid rhythm guitar playing, and songwriting endeared him to generations of bluegrass and country music fans. A member of the classic edition of Bill Monroe and the Blue Grass Boys, Lester’s star burned even hotter when he and Earl Scruggs formed a partnership in the 1940s, heading the Foggy Mountain Boys. Mercury and Columbia records, WSM radio, the Grand Ole Opry, constant touring, a Martha White Mills-sponsored television show, themes to “The Beverly Hillbillies” and “Bonnie & Clyde,” and full participation in the folk revival ever widened Lester Flatt’s visibility and influence. After splitting with Earl Scruggs in 1969, Lester headed a crack bluegrass ensemble, the Nashville Grass, on Nugget, RCA, and CMH records right up to the year of his death at the age of 64 in 1979.

Lester Flatt was born to a musical farming family in central Tennessee, near Sparta. He started on banjo, but switched to guitar at the age of seven. Lester played with a thumb and finger pick, as did most country guitarists in the 1930s and 1940s. He left school at 12, married singer Gladys Stacey at 17, and alternated between textile millwork and music for a decade before committing to a professional music career after a bout with rheumatoid arthritis. Lester sang tenor, first with Clyde Moody and then with Charlie Monroe, before permanently switching to lead upon joining the band of Charlie’s younger brother Bill in 1945.

“A Conversation with Lester Flatt,” interview with Vernon, Bill in Muleskinner News, August, 1972.

It must have been a heady experience appearing on the Grand Ole Opry and recording for Columbia records in Chicago with the Blue Grass Boys. But by this time Lester Flatt was a seasoned professional, and emceed stage shows for the more reticent Monroe. Like contemporaries Frank Sinatra with the Harry James and Tommy Dorsey bands, and Tommy Duncan with Bob Wills and the Texas Playboys, Flatt was prominently featured as a crooning vocalist. Lester’s wife missed him during the long road tours, and soon was also employed by the Monroe organization, selling concessions. When banjo player Stringbean left the group, Flatt didn’t share Monroe’s enthusiasm for finding a replacement – until he heard young Earl Scruggs play the instrument in an exciting new style at an impromptu backstage audition. In a 1979 interview with Don Rhodes for Pickin’, Lester recalled telling Bill, “Hire him no matter what it costs.”

After three years of stardom as sidemen, Flatt and Scruggs decided that they were ready to co-lead their own organization. In 1948, they founded the Foggy Mountain Boys. Relations with their former employer were cordial until 1955, when Martha White Mills insisted on Flatt and Scruggs’ addition to the cast of the Grand Ole Opry. Bill Monroe considered this direct competition for his niche and tried to block the decision, but was unsuccessful. He and Flatt didn’t speak until a 1973 reconciliation at Bean Blossom, Indiana.

The Foggy Mountain Boys worked hard at a series of small radio stations before landing a 15-minute, 5:45 am slot in 1953 on WSM: “Martha White Biscuit Time.” This, and a television show which followed two years later, were syndicated to other southern markets. But technology at the time forced the group to travel to these locations for the broadcasts. A bus was fitted out for the band and they traveled more extensively than any other Grand Ole Opry act.

Lance LeRoy, quoted in Willis, Barry R., America’s Music: Bluegrass, 1989.

Hugely successful for two decades on the air, on records, and on stage, Flatt and Scruggs finally split in 1969 after differences about musical direction. Earl wanted to play more modern music with his sons. Uncomfortable singing Bob Dylan and other folk material demanded by a Columbia record contract, Flatt headed off on his own to play a much more traditional brand of bluegrass. Martha White sponsored a “name the band” contest. The winning name, “Nashville Grass,” was a pun on the currently popular Danny Davis and the Nashville Brass.

Lester Flatt made some strong recordings as a solo act, including three albums of duets with former associate Mac Wiseman. His appearances, with a strong ensemble of side musicians, were enthusiastically received on the burgeoning bluegrass festival scene. But health problems arising from a 1967 heart attack led to an open-heart operation, lowered stamina, reduced touring, and eventual retirement early in 1979. Flatt persuaded Curly Seckler to continue the Nashville Grass, and died a few months later. In her song, “The Day That Lester Died,” Claire Lynch spoke for the entire bluegrass community, “The songs will live on, we’ll sing them again, but somehow it will never be the same.”

“A Conversation with Lester Flatt,” interview with Vernon, Bill in Muleskinner News, August, 1972.

– Reproduced from the Lester Flatt entry on the Hall of Fame Inductees page of the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame & Museum website

While we eventually found Lester Flatt’s final resting place, we had no such look in other searches.

Benny Martin, a boyhood friend of Lester Flatt, was a local Sparta boy, too (as is Blake Williams, a Bill Monroe Blue Grass Boy for a decade and Lester Flatt’s last banjo picker, and Josh Swift, IBMA’s 2017 Dobro Player of the Year and former member of Doyle Lawson’s Quicksilver). Not that you’d know it after a snoop around charming present-day downtown Sparta – it’s Lester Flatt that gets all the attention around here, or at lest that’s how it looked to us. We couldn’t find any reference – no monument, no plaque, nothing – to Bluegrass USA’s other bluegrass Hall of Famer and Grand Ole Opry member, the inventor of the 8-string fiddle and one of the premier and more flamboyant fiddlers from the golden age of bluegrass and country music who performed and/or recorded with a number of seminal first-generation bluegrassers including Bill Monroe, Flatt & Scruggs, the Stanley Brothers, and Don Reno.

Quite the oversight we think, Sparta.

Maybe we just didn’t look hard enough.

Next time.

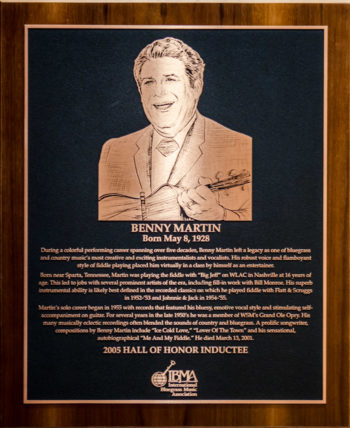

Benjamin Edward "Benny" Martin | IBMA Hall of Fame Bio

Quoted by Earl V. Spielman, in liner notes to Benny Martin, The Fiddle Collection, CMH 9006, 1976.

IBMA Hall of Fame Induction | 2005

IBMA Hall of Fame Induction | 2005

Born | May 8, 1928 in Sparta, Tennessee

Died | March 13, 2001 in Nashville, Tennessee

Primary Instrument | Fiddle

Benny E. Martin was born in Sparta, Tennessee, the hometown of legendary bluegrass singer Lester Flatt. He came from a musical family and received a fiddle at age 6 or 7. He had several teachers/mentors early on, including local fiddlers Carl Orvison and Louis Armstrong (not the famous trumpeter, but an African-American). By age 8 or 9, he was performing in the family’s band, the Martin Family, on radio station WHUB in Cookeville, Tennessee, and making Saturday evening appearances at the Upper Cumberland Jamboree.

In the early 1940s, he would hitchhike to Knoxville to be near the radio powerhouse WNOX, which at various times was home to Molly O’Day, Chet Atkins, Charlie Monroe, Jethro Burns, Bill Carlisle, and others. While there, he was given employment by gospel singer Wally Fowler.

Benny Martin, in liner notes to The “Big Tiger” Roars Again, Part 1, OMS 25010, 1999.

A year or so later, Big Jeff Bess discovered Benny in Knoxville and took him back to Nashville. There, he appeared with Big Jeff & the Radio Playboys on WLAC. While in Nashville, he did some brief work with several Grand Ole Opry acts, including Robert Lunn, Curly Fox, and the blackface comedy duo of Jam Up and Honey, with whom he made his first Opry appearance in 1946. It was also in 1946 that Benny released his first record, on the Pioneer label: “Me and My Fiddle” b/w “So Blue to Cry.”

The Opry continued to be an important outlet for work. In 1947, he performed and recorded with Red Foley. Later in the year, he hooked up with Bill Monroe & the Blue Grass Boys (which included Lester Flatt, Earl Scruggs, and Cedric Rainwater). He stayed with Monroe into 1948, even after the departure of Flatt and Scruggs, and was part of Monroe’s next classic group – that which included Don Reno and Jackie Phelps.

Benny’s next move was to Roy Acuff and the Smoky Mountain Boys. He participated in some of Acuff’s later recordings for Columbia. It was while working for Acuff, in February of 1951, that he signed with MGM as a solo artist. He had two discs released on that label: “Midnight Flyer” b/w “Where Is Your Heart Tonight?” and “The Thirteenth of May” b/w “Tryin’ to Chase the Blues Away.”

By the middle of 1952, Benny was reunited with Lester Flatt and Earl Scruggs as a member of the Foggy Mountain Boys. He joined the group when they were working at WNOX. Everett Lilly was playing mandolin at the time and Little Darlin’ (Charles Elza) was doing comedy. He recorded two sets of sessions with the group. On November 9, 1952, he recorded “Why Did You Wander,” “Flint Hill Special,” “Thinking About You,” “If I Should Wander Back,” “Dim Lights, Thick Smoke,” “Dear Old Dixie,” “Reunion in Heaven,” “Pray For the Boys.” On August 29 and 30, 1953, he recorded “I’ll Go Stepping Too,” “I’d Rather Be Alone,” “Foggy Mountain Chimes,” “Someone Took My Place,” “Mother Prays Loud,” “That Old Book of Mine,” “Your Love is Like a Flower,” and “Be Ready For Tomorrow.” Benny was always very candid about his struggles with alcohol over the years, and he readily admitted that this was the reason for his termination with the group.

It was Benny’s playing on the Flatt & Scruggs recordings that endeared him to generations of bluegrass fans. It’s generally agreed that he played good and loud, favoring double stops (multiple notes), with a lot of pressure applied to the strings by the bow. John Hartford observed that Benny put “as much emotion as I have ever heard any one human being put into music… His bow licks, timing and syncopations are the key to what he’s doing… His accenting and slides are very important, his way of pushing the beat ever so slightly for energy.”

John Hartford, “Benny Martin: The Genius of Music City, USA,” Fiddler Magazine, Fall 1999.

When he left Flatt & Scruggs, he went next to the duo of Johnnie & Jack. Their fiddle player at the time was Paul Warren, who left their group to play with Flatt & Scruggs. In essence, the two groups traded fiddlers. From February of 1954 through July of 1955, Benny recorded seven sessions with Johnnie & Jack, cutting 17 songs in all. Among the tunes he recorded were “Goodnight, Sweetheart, Goodnight,” “Sincerely,” “Carry On,” and “Look Out.” As Johnnie Wright was married to Kitty Wells, Benny wound up recording two sessions with her on Decca, including one of her biggest hits, “Makin’ Believe.”

While working for Johnnie & Jack, Benny signed a two-year recording contract with Mercury Records, recording as a solo. His first session was in August of 1954. In all, he had 21 songs that were released. He played guitar and sang on all the selections, leaving the fiddle chores to Nashville session players Dale Potter, Grover “Shorty” Lavender, or Howdy Forrester. However, Benny did play fiddle on a remake of “Me and My Fiddle.”

Benny embarked on a solo career after leaving Johnnie & Jack. He signed a management agreement with Hal Smith in the latter part of 1955 but soon afterwards switched to Col. Tom Parker, the promoter who oversaw Elvis Presley’s early rise to fame. Benny appeared as an opening act for Elvis on about 50 show dates in 1955 and early 1956. It was also during this period that Benny became a member of the Grand Ole Opry, having been signed by Jim Denny, who was in charge of the WSM Artists Services Bureau. This led to his appearing on a lot of Opry tours over the next several years.

In 1957, Benny switched from Mercury to RCA and recorded several singles. Unfortunately, these failed to attract much attention. He continued touring and did a considerable amount of session work in Nashville. One memorable session occurred in November of that year when he and Howdy Forrester played twin fiddles on a Stanley Brothers session for Mercury; included was the classic instrumental “Daybreak in Dixie.”

Benny signed with Starday in 1960 and recorded about 40 songs and tunes for the label. He had eight singles and one album – Country Music’s Sensational Entertainer – released on the label. But, perhaps more importantly, his music was sampled on at least 30 different various artists’ collections on Starday and its budget label, Nashville. Consequently, his music was appearing with other artists on a diverse set of albums with titles such as Nashville Saturday Night, More Country Music Spectacular (a 2-LP set), Opry Time in Tennessee, and Fiddler’s Hall of Fame.

By 1965, he was done with touring in Opry package shows. He returned to his bluegrass roots, teaming up with Don Reno for a short-lived duo. They appeared at the first multi-day bluegrass festival, on Labor Day weekend in 1965, and recorded an album of gospel songs for the Cabin Creek label.

Frank J. Godbey, record review, Bluegrass Unlimited, February, 1980.

Benny’s career was much less defined for the next three-and-a-half decades. He didn’t tour much and he admitted that his drinking and no-show reputation hurt him professionally. He did tour briefly with Lester Flatt in 1977, filling in for in for Paul Warren. With the help of Alcoholics Anonymous, he finally got his drinking under control and cited November 14, 1978 as the day he took his last drink.

When John Hartford moved back to Nashville in the 1970s he befriended his childhood idol Benny Martin. John was a major patron for Benny in the last decades of his life, arranging and producing recording sessions for him and promoting his legacy and prodigious talents, within a community and industry that looked upon Martin as a has been.

The 1970s were witness to a number of fine recordings. In contrast to his solo recordings of the 1950s, Martin’s new efforts saw his return to the fiddle. One of the first, and best, was a collection on Flying Fish (1975) called Tennessee Jubilee, with guest artists Lester Flatt, John Hartford, Curly Seckler, Kenny Ingram, Charlie Collins, and others. A series of albums and double-album sets followed on the CMH label: The Fiddle Collection (1976), Benny Martin and his Electric Turkeys: Turkey in the Grass (1977), Big Daddy of the Fiddle and Bow, with John Hartford and Bobby Osborne (1979), and The Great American Fiddle Collection, with Buddy Spicher (1980). Also recorded was one additional release for Flying Fish, Slumberin’ on the Cumberland (1979).

In 1980, Benny was diagnosed with Spasmodic Dysphonia, a “voice disorder characterized by involuntary movements of one or more muscles of the larynx during speech.” As Benny put it, it’s a “nerve disorder, or a dystonia, that gradually paralyzes the larynx.” It “destroyed” his singing and likely accounts for the dearth of new recordings from 1980 until 1999. The disorder spread to his eyes and made it difficult to keep them open. Consequently he wore a bandana tied tightly around his head, which had the effect of holding his eyelids open.

Benny finished his recording career with a pair of CDs that were issued in 1999 and 2001. Called The “Big Tiger” Roars Again, Part 1 and The “Big Tiger” Roars Again, Part 2, these discs were star-studded events that recalled several of his musical triumphs of the past and paired them with new material. Benny won an IBMA award for Best Liner Notes for Part 1.

Benny died in 2001 of congestive heart failure. He was inducted posthumously into the International Bluegrass Music Museum’s Hall of Fame in 2005. Today, Benny Martin’s legacy is well established among generations of bluegrass fiddlers who cite him as an influence, including notably Michael Cleveland and Jason Carter.

– Reproduced from the Benjamin Edward “Benny” Martin entry on the Hall of Fame Inductees page of the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame & Museum website

0 Comments