Hyden, KY | #BluegrassTrails

Part of the mygrassisblue.com #BluegrassTrails series, on the trail of bluegrass history and its pioneers/early protagonists.

Osborne Brothers Way outside Hyden, Kentucky, hometown of Sonny & Bobby, The Osborne Brothers. October 18, 2017.

City Hall, Hyden, Kentucky, hometown of Sonny & Bobby, The Osborne Brothers. October 18, 2017.

Hyden, KY, & The Osborne Brothers Hometown Festival

‘In The Heart of The Mountains’ and the county seat of Kentucky’s dry Leslie County, which bills itself as ‘The Redbud Capital of the World’, Hyden was established in 1878 and has since had not one but two rather large moments in the national spotlight: In December 1970 as the nearest settlement to the Hurricane Creek mine disaster, which killed 38 miners and was immortalised in the Tom T. Hall’s song ‘Trip to Hyden’; and again in 1978 when ex-president Nixon made his first public speech here after his resignation following the Watergate scandal.

Firmly on the bluegrass map, the town hosts a popular multi-day annual bluegrass festival, The Osborne Brothers Hometown Festival, at the town’s Bobby Osborne Pavilion. The festival started in 1994 as a benefit for the Thousandsticks Volunteer Fire Department meaning Hyden hosted its 25th festival in August of 2018. Festival weekend is probably as good a time as any to visit the town. If doing so you should find it a tad livelier than we found late on a mid-October afternoon.

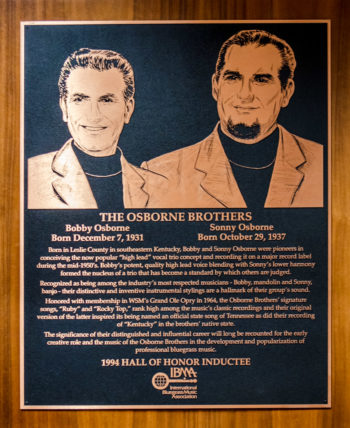

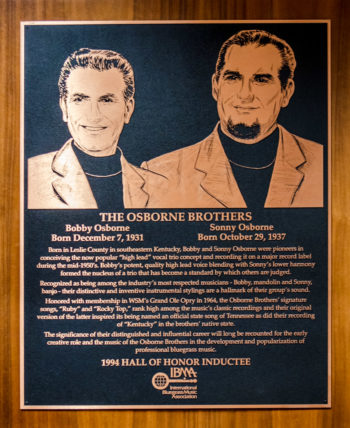

Bobby Osborne | IBMA Hall of Fame Bio

Neil Rosenberg, bluegrass historian, 2009

IBMA Hall of Fame Induction | 1994

IBMA Hall of Fame Induction | 1994

Born | December 7, 1931 in Hyden, Kentucky

Primary Instrument | Mandolin

Bobby Osborne was born to a schoolteacher/grocer in Depression-era eastern Kentucky. Like so many others from that region, the family migrated to industrial areas in the early 1940s, winding up in Dayton, Ohio. Robert Osborne, Sr. blended a job at NCR Corporation with part-time farming. In free moments, he enjoyed singing, yodeling, and playing guitar in the style of the Carter Family and Jimmie Rodgers. He taught rudimentary chords to his namesake and oldest son, who preferred the popular Grand Ole Opry artists of the day, particularly Ernest Tubb.

All three children (Bobby, Louise, and Sonny) were musical. In 1947 they were bitten by the bluegrass bug after attending a sold-out Dayton performance by Bill Monroe’s classic band. Bobby got a thumb pick and a Martin guitar like Lester Flatt’s, but found that his emerging adult voice was as high, or higher, than Bill Monroe’s.

Still underage, he began performing with like-minded neighbors at a bar. In 1949, a small-time talent scout took him to WPFB in Middletown, where Bobby’s first broadcast produced quite a local stir. Larry Richardson, a hot young banjo player from Galax, Virginia, came to Middletown, teaming with Bobby in several groups, culminating in several years with the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers. Larry and Bobby converted the group from a style similar to the Delmore Brothers to the increasingly popular (but as yet unnamed) bluegrass sound. Their song, “Pain in My Heart,” recorded for Cozy in 1950, was covered by Flatt & Scruggs later in the year during their final sessions for Mercury.

Jimmy Martin, fresh from his first stint as guitarist/lead singer with Bill Monroe, joined the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers in June of 1951. Bobby switched from guitar to mandolin, and soon arranged to record four songs with Jimmy under their own names for the King label in Cincinnati. After Jimmy left for Knoxville, Bobby played three weeks with the Stanley Brothers before joining the Marines for combat duty in the Korean conflict. Wounded in Panmunjon, he returned to the front until his discharge in late 1953.

Quoted in Barry R. Willis, America’s Music: Bluegrass, 1989.

By the time Bobby returned to Dayton, his younger brother Sonny had developed into a teenaged banjo prodigy, including a stint touring and recording with Bill Monroe. Bobby appeared as an uncredited guest on Sonny’s later sessions for Gateway in Cincinnati. Jimmy Martin came to southwestern Ohio and joined with Bobby and Sunny as Jimmy Martin and the Osborne Brothers. They started at WPFB in Middletown, then moved to WJR radio in Detroit and CKLW television in nearby Windsor, Ontario. A recording contract with RCA Victor produced “20-20 Vision” and five other scorching bluegrass classics.

By early 1956, the brothers were back in Dayton, where they met and formed an act with lead singer/guitarist and fellow Kentuckian Red Allen. A local DJ got them an audition with MGM and “Once More” broke out as a #13 country single. As good as they were — and their playing and harmony singing were truly unique — all bluegrass and classic country artists were facing increasing competition from the youth music preferred by emerging baby boomers. By 1958, Red Allen was gone. Bob’s voice became the center of the act, which was henceforth known as the Osborne Brothers.

They kept the banjo, mandolin, and the high lead trio, but increasingly experimented with material and backup instrumentation that could penetrate rockabilly, folk, and modern country markets. The Wilburn Brothers became the Osborne Brothers’ business mentors, and by 1964 Bobby and Sonny had moved to Nashville, joined the Grand Ole Opry, and signed with Decca (later MCA) records.

Quoted in Barry R. Willis, America’s Music: Bluegrass, 1989.

The career hit “Rocky Top” came in 1968. Written by Felice and Boudleaux Bryant, it was recorded over the objection of the Wilburn Brothers and considered at the time by the Osborne Brothers to be “just another bluegrass song.” Within 10 days it had sold 85,000 copies and it stayed in the Billboard charts for 10 weeks.

Twelve more top-100 country hits – five of them penned by the Bryants – followed in as many years. Mass-market radio play, a rarity for bluegrass artists, opened the door to lucrative package tours. But the brothers found that the PA systems of the time failed to project their acoustic instruments. With pickups, electric bass, and eventually drums, they were able to hold their own against the louder acts with whom they shared the stage.

After five years playing through pickups, Bob and Sonny removed them in 1974. By 1991, the last vestige of amplification was gone from the group. In other ways, the band returned to the classic approach with which they had begun. As country and folk audiences turned elsewhere, the bluegrass market was increasingly able to offer a sustainable if modest living, through its own festival and performance circuit, record labels, radio programs, and publications.

The Osborne Brothers’ career hardly stagnated as the second millennium reached its end. Bluegrass was spreading worldwide, and the Osbornes made several international tours. In 1982, “Rocky Top” was named an official song of Tennessee. In 1992, the Osbornes’ arrangement of “Kentucky” led to a similar honor from the state of their birth. Bobby and Sonny mentored young musicians (notably the Grascals), and produced and recorded with others – including the bluegrass/hip hop fusion GrooveGrass Boyz. Bobby’s duet mandolin performance of “Ashokan Farewell” was on the 2000 IBMA Instrumental Album and Recorded Event of the Year.

A half-century musical partnership between the brothers came to an end when Sonny Osborne’s rotator cuff surgery forced him to stop playing the banjo and leave the road. Bobby continued by forming his own band, the Rocky Top X-Press. With son Bobby Osborne, Jr. on guitar, Bobby maintains an extensive schedule of performances, Grand Ole Opry appearances, and recordings on the Rounder label.

Quoted in Rounder Records promo sheet for the album “Bobby Osborne: Try a Little Kindness,” 2006.

– Reproduced from the Bobby Osborne entry on the Hall of Fame Inductees page of the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame & Museum website

Sonny Osborne | IBMA Hall of Fame Bio

IBMA Hall of Fame Induction | 1994

Born | October 29, 1937 in Hyden, Kentucky

Primary Instrument | Banjo

Sonny Osborne was born in the coalfields of eastern Kentucky. Like so many others from that region, the family migrated to industrial areas in the early 1940s, winding up in Dayton, Ohio. His father, Robert Osborne, Sr., blended a job at NCR Corporation with part-time farming. He loved country music and transmitted that love to three children: Bobby, Louise, and Sonny.

By 1949 Bobby was a professional musician, performing with the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers in West Virginia. In the sixth grade, Sonny became interested in the banjo and convinced his father to purchase an inexpensive starter instrument. Before it arrived, Sonny visualized how to play two pieces, the Stanley Brothers’ “We’ll Be Sweethearts in Heaven” and “Cripple Creek.” He surprised himself and his family by playing them the day the package arrived. As he later described in the autobiographical “Me and My Old Banjo,” Sonny became obsessed, practicing eight to 15 hours a day until he felt ready to perform in public.

Ott Ginter, a neighbor, took the banjo prodigy to the WPFB Jamboree in nearby Middletown, Ohio, and released four home recordings on the Kitty label under the name “Lou and Sonny Osborne.” These included Louise’s composition, “New Freedom Bell.” Also performing were brother Bobby and Jimmy Martin, who had joined the Lonesome Pine Fiddlers in 1951.

Sonny was a talented athlete. He played varsity football in high school, but music remained his first interest. During Sonny’s summer vacation before the 10th grade, Jimmy Martin took him to see Bill Monroe at Bean Blossom, Indiana. There, Jimmy decided to return to the Blue Grass Boys and convinced Bill to take the 14-year-old banjo player as well. In July of 1952, they recorded nine songs and instrumentals for Decca, including Bill’s “Memories of Mother and Dad,” “The Little Girl and the Dreadful Snake,” and “Pike County Breakdown.”

Interview with Neil Rosenberg in “The Osborne Brothers,” Bluegrass Unlimited, September, 1971.

The next school year was tumultuous for Sonny. Bobby was fighting in Korea with the Marines. The family moved from the farm back to Dayton, where Sonny met Judy, the girl from across the street who later became his wife. He recorded three sessions under his own name for the Gateway label in Cincinnati, including “Sunny Mountain Breakdown,” which sold some 67,000 copies. And when Bill Monroe came through Toledo in need of a banjo player, Sonny left school to pursue music full-time.

When Bobby left the military, the brothers first played together in Knoxville, Tennessee, on November 6, 1953. Unable at first to sustain an act on their own, Sonny and Bobby teamed with Jimmy Martin for a year, Charlie Bailey for a few months, and Red Allen from early 1956 to mid-1958. During this period, they gained valuable performing and business experience, radio and television exposure, and recorded for nationally distributed labels RCA and MGM. Sonny became famous as a cutting-edge banjo player and harmony singer, but the Osborne Brothers’ ace in the hole was Bobby’s stunningly high and clear voice.

Devotedly loyal to his elder brother, Sonny worked tirelessly to build the act as a commercially viable package. Interested in a wide variety of music, it was Sonny who brought to their sound elements of rock ‘n roll, rhythm and blues, modern country, pop, folk, and jazz. As each Osborne Brothers record was released, banjo fans would delight in discovering the new licks Sonny had adapted from horn, keyboard, lead and steel guitar, and even percussion players. Sonny was also principal architect of some of the most complex and effective trio vocal arrangements ever recorded in bluegrass or country music.

In 1963, after a decade of effort to carve a niche in the music business, the brothers were still driving and maintaining taxicabs in Dayton to make ends meet. Sonny found Doyle Wilburn’s business card and called him from a motel in Chester, Pennsylvania. Within days, Wilburn had arranged a guest spot on the Grand Ole Opry. In the next year, under the tutelage of the Wilburn Brothers, the Osborne Brothers had a contract with Decca, a permanent berth on the Opry, radio airplay, a publishing contract, and bookings in more upscale settings.

Quoted by Glenna H. Fisher in “The Osborne Brothers,” Bluegrass Unlimited, July, 1984.

Some of the Osborne Brothers’ most popular songs as country/bluegrass artists included “Ruby Are You Mad,” “Once More,” “Rocky Top,” “Making Plans,” “Up This Hill and Down,” “Midnight Flyer,” “Muddy Bottom,” “Tennessee Hound Dog,” “Georgia Pineywoods,” and “I Can Hear Kentucky Calling Me.” They played major country package shows and bluegrass festivals, bringing to both the same brand of high-powered, crowd-pleasing entertainment: Sonny’s banjo, Bobby’s mandolin, perfect vocal harmony and — for a time — amplified instruments, electric bass, and drums.

Interview with Eddie Stubbs, quoted by Marty Godbey in liner notes to “The Osborne Brothers: Decca/MCA Recordings, 1968-1974,” Bear Family Records, 1995.

A changing country marketplace and the brothers’ lifelong preference for bluegrass brought them back to an all-acoustic act by the 1990s. Audiences at festivals and concert appearances welcomed the traditional sounds. A string of Osborne Brothers albums for niche labels CMH, Sugar Hill, and Pinecastle exposed primal bluegrass to those who weren’t alive for the classic bands of the ‘40s and early ‘50s. Sonny and Bob continued to attract young and talented disciples, eager to apprentice on touring appearances and recording sessions with the well-known masters.

Letter to the editor, Bluegrass Unlimited, June, 1967.

Sonny Osborne found a side career in producing recording sessions for emerging artists, including the Pinnacle Boys, the Virginia Squires, Terry Eldredge, and Dale Ann Bradley. A half-century musical partnership between the brothers came to an end when Sonny Osborne’s rotator cuff surgery forced him to stop playing the banjo and leave the road in 2004. Sonny remains active in musical affairs, distributing a line of banjos branded with his nickname, “Chief.” Always outspoken, Sonny continues to advocate for high standards in bluegrass and respect for the founding pioneers, who struggled with little reward to create an art form and industry with worldwide impact.

– Reproduced from the Sonny Osborne entry on the Hall of Fame Inductees page of the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame & Museum website

Elsewhere | Video

Bobby interviewed in 2012 by guest host Glen Duncan for Rural Rhythm’s Behind The Dream, and broadcast as part of Season 1 of the Bluegrass Music Show. During the interview he reminisces, among other things, about his early career as a cab driver in Dayton, Ohio; about the Osborne Brothers first appearance on the Grand Ole Opry, where he sang “Ruby” for the first time on that sacred stage; and about his first time hearing Bill Monroe on the radio. (25 minutes 12 seconds)

Sonny Osborne, in a video entitled ‘Banjo Legends’, with two renditions of ‘Cripple Creek’ at, what appear to be, either end of his long and illustrious career. As per the above bio, ‘In the sixth grade, Sonny became interested in the banjo and convinced his father to purchase an inexpensive starter instrument. Before it arrived, Sonny visualized how to play two pieces, the Stanley Brothers’ “We’ll Be Sweethearts in Heaven” and “Cripple Creek.” He surprised himself and his family by playing them the day the package arrived.’ (5 minutes 8 seconds)

Elsewhere | Podcast

In Season 1 of the Walls of Time Bluegrass podcast, host Daniel Mullins sat down and chatted with Sonny Osborne about his life and times in the music industry. The interview, entitled ‘Risks Worth Taking’, was released as a two-part podcast and is well worth two hours of your time.

Part 1 | S1 E15 | November 19, 2019

– From the podcast:

‘There is no bigger living legend in bluegrass than banjo great Sonny Osborne. Along with his brother Bobby, they formed the Osborne Brothers in the 1950’s and went on to become one of the most influential artists in the field. Huge hits like “Rocky Top” helped make them a household name. Sonny retired from music in 2003, but his legacy lives on as both a member of the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame and the Grand Ole Orpy. Daniel Mullins sat down with Sonny on his back porch for a two-part interview during a rainy Saturday afternoon at his home outside of Nashville, TN. Sonny shares his knowledge of the music industry, his business savy and his personal musical history with fellow legends like Bill Monroe, Jimmy Martin and more. Let’s head to Sonny’s back porch for this episode of Walls of Time.’

>>> Listen (1 hour 7 minutes)

Part 2 | S1 E16 | November 22, 2019

– From the podcast:

‘Few banjo players have impacted American music like Sonny Osborne has. The Osborne Brothers’ success includes multiple country radio hits, working with Merle Haggard, international tours, being members of the Grand Ole Opry, winning a CMA award, and induction into the Bluegrass Music Hall of Fame. Sonny’s banjo playing is some of the most influential in bluegrass music. In part two of this interview on Walls of Time, Sonny shares his thoughts on bluegrass and banjo playing, behind-the-scenes stories about the mighty Merle Haggard, and opens up about his struggles with addiction. Let’s re-join Daniel Mullins on Sonny Osborne’s backporch during a rainy afternoon, for the second half of our conversation with Bluegrass Hall of Famer, Sonny Osborne.’

>>> Listen (50 minutes)

Elsewhere | Online

BobbyOsborne.com & SonnyOsborne.com

BobbyOsborne.com : Bio, Honors, Awards and whatnot. It hasn’t been updated in a while (since late 2017 as of August 2020), but it’s still the home of Bobby Osborne on the internet.

SonnyOsborne.com : There’s not a whole lot going on here at Chief Banjo, but again it is, we assume, Sonny Osborne’s (sparsely furnished) home on the internet.

Bluegrass Today’s ‘Ask Sonny Anything…’

There’s plenty going on here. Essential reading for all bluegrass fans, BT’s ‘Ask Sonny Anything…‘ segment, published weekly on a Friday, sees Sonny answer reader questions in a open and forthright way. As we said, interesting insights aplenty and essential reading.

0 Comments